RAPHAELA HOPSON

Raphaela Hopson lives in London with her f***ing breathtaking mother, socially-inept stepfather, mighty younger sister, other just-as-mighty younger sister, hyperactive dog and their cat, who is a serial killer. She’s looking to move out.

After graduating from the University of East Anglia with a first-class honours in English Literature with Creative Writing (which included a six-month residency in San Francisco), she moved to Florence to complete her Master’s in Visual Art from the Accademia D’Arte. She has been published in Ambit Magazine, Transfer 115 and UEA’s Underpass. She was awarded The University of East Anglia Jarrold Prize, The Malcolm Bradbury Award and has survived three (fairly minor) earthquakes.

In her work she is trying in vain to capture the beauty of Michelangelo’s Pieta, the honesty of Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag and the sickly-sweet intensity of Limoncello that hits the back of your throat and sets fire to your organs.

“This collection is an exploration into loneliness, human intimacy and the chaos of living in your own head”.

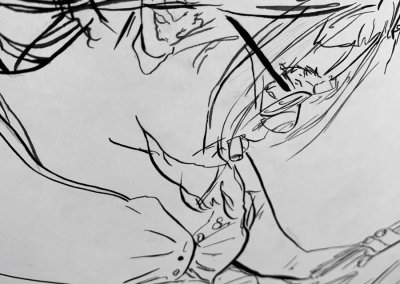

Raphaela Hopson develops her artistic research using written texts and drawings, the two media are complementary: both aim to describe – I would say in an imaginative and evocative rather than analytical way – real situations related to contemporary society. If the artist’s practice in other phases turned outward (scenes of life in the street, in a supermarket, in other places of everyday life) in this case, given the quarantine situation, she focused on what was happening inside her own home: therefore the continuous cohabitation of the various members of the family, within a completely new situation of waiting.

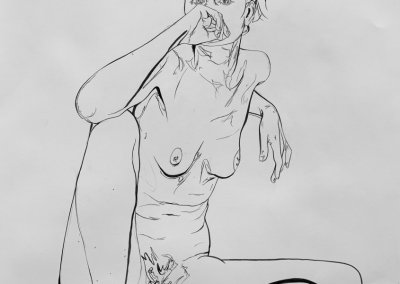

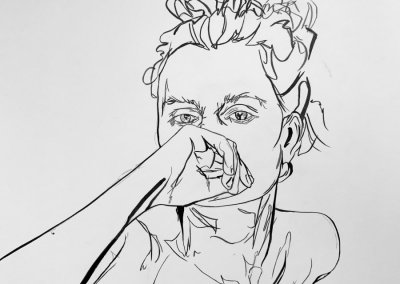

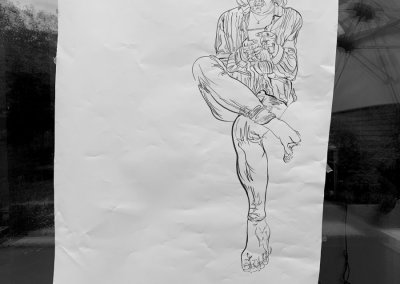

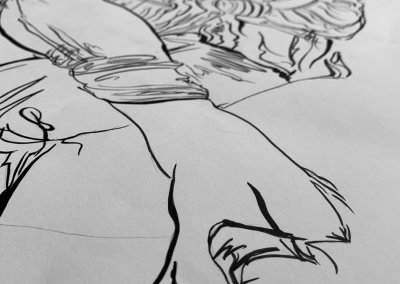

On the one hand, there are some large drawings on paper, which are portraits of family members caught in random activities (or stasis): the figures seem to “float” in the white space around them since only the bodies are drawn – nothing appears of their environment, no architecture, no object – but this does not concern the dimension of the possibilities, since in reality the white becomes a strong, almost oppressive presence, and the set of lines that form the bodies – broken, jagged – give a sense of subtle restlessness (who has not experienced this in recent months?).

On the other hand, the Devorshire Road 229 series is like a narrative in fragments, each one very significant. Some family portraits mark a stream of written thoughts: they are similar to letters (typewriter is replicated by hand, which creates a strong connection between writing and drawing, as we said at the beginning). Such letters are ideally sent by the artist to herself, to her own address: communication creates a short circuit because, in a period of uncertainty, exploration is first of all about our intimacy, that is to say, it becomes self-reflection – which never gives up a dose of irony, a quote for example “I hate it when people tell me I overthink things because that means I then have to think about how much time they have spent thinking about me thinking about things…”.